1. ‘Sensible Difference’

In versification there is a sensible difference between softness and sweetness that I could distinguish from a boy. Thus on the same points, Dryden will be found to be softer, and Waller sweeter. It is the same with Ovid and Virgil; and Virgil’s Eclogues, in particular, are the sweetest poems in the world. POPE, 1-7 May 1730

Joseph Spence, Observations, Anecdotes, and Characters of Books and Men, ed. James M. Osborne, 2 vols. (Oxford, 1966), I.176.

What is the sensible difference between softness and sweetness in verse? How is it felt? And by what artifice is verse made soft or sweet? Alexander Pope himself, who might have been the best qualified person to answer these questions in the history of English poetry, seems not to have been very interested in explaining his ideas concerning matters of this kind in detail. Like many serious poets he appears to have preferred to court readers who had the gift of getting it for themselves; readers capable of sensing what Denise Riley, a serious poet who doesn’t mind explaining things sometimes, teaches us to call the linguistic affect of a poem, without needing to be told what they were meant to be feeling; readers who could receive a poem in its fullness without having the mechanism of its action broken down for them. Pope’s friends and nearest contemporaries weren’t much more helpful — at times it seems almost as though they were afraid their ideas about poetry contained something shameful or dangerous that they needed to hide from those outside their circle. And although for some years after Pope’s death an explanatory discourse about his verse was kept up in which such questions were addressed, or at least could and should have been, very little was done to take Pope’s own most distinctive ideas seriously.

That strangely muted discussion of Pope’s work in the second half of the eighteenth century was arguably the first sustained attempt at a public critical discourse about a major poet’s verse wholly within and about English vernacular poetics. It was the first such discourse which could not justifiably turn to classical or continental precedent or precept for its answers, as the overdetermined and dogmatic discourse on Milton’s verse had done, because Pope’s verse was almost completely outside the parameters of precedent in its control and variety of effect. Participants in this discourse — including such sensitive readers as Joseph Warton, Samuel Johnson and Henry Home, Lord Kames — were therefore obliged to look directly into Pope’s verses to discover the method by which Pope had managed to make them move and feel as they did. But such inquiry proved difficult. Pope’s poems were too much for the comparative reductions on which eighteenth century critical prose relied. Their prevailing ironies caused serious trouble for an idiom intended to frame the acts of criteriological sorting and grading which preoccupied early modern humanist scholars and their heirs. To write with truth about how Pope’s verse made its most sensitive readers feel would mean breaking the rules governing conduct in polite letters. It would mean talking about inwardness, especially male inwardness, in a way they were only accustomed to accept, or more often to ridicule, as a privilege of enthusiasm or imposture of madness.

⁂

Although it may prove interesting for what I want to say further down the line in my reflections on the poetics of softness that Pope’s sensitive male readers were also resistant readers, such limitations rendered the immediate critical discourse on Pope’s verse a failure. Its most telling insights were typically offered under the cover of denials, in fragments and doodles. Eighteenth century literary criticism simply did not have a language through which to represent and to discuss verse-sensation in a satisfactory way. Effects needed to be linked to clear causes, to have clearly definable lines of development, and to correspond with ideas — typically predetermined and by later standards simplistic — about who should be feeling what, when, and why. Pope’s verse, which I believe started from a very different set of assumptions about the things sensitive readers might do with poems, therefore rendered even the best writing about his poetry from within the fold of his own culture’s literary criticism inane. Without a lot of reading-in and reading-between-the-lines on our part, even a critical reader so emotionally present in his storytelling as Samuel Johnson appears stuck repeating banalities when it comes to verse-sensation in Pope’s work, connecting strong cadence with strong passion, making scarcely relevant pronouncements about poetry in general, and scolding Pope on thinly disguised sectarian grounds. It was impossible for readers so inhibited by restrictive codes of masculinity, rhetoric, and religious prejudice to write about Pope as a serious poet, even if such readers might have a sense that something serious had happened to them when they looked into his work. Pope’s seriousness led in another direction completely. And so beyond disconnected insights, which rarely ramified as they could and should have done in their writings, Pope’s best early critics, particularly those among his male readers, completely failed to explain what exactly Pope’s verses felt like, let alone how they were made, or what the connections between these two moments, the feelings of reader and the methods of the poet, might imply.

The resulting lack of an adequate critical supplement to his work, whether by Pope or anyone else, helped to promote in various forms the question of whether or not Pope was an ‘essential poet’, or just a kind of translator who rendered other people’s thoughts ‘into the language of poetry’, as the selectively cloth-eared Coleridge would allege. When a revolution in literary criticism came in the wake of Coleridge’s work in the next century, and acts of reading started to be represented with a more searching interest in the truth of the critical reader’s experience, Pope would be positioned as an uninteresting literary curiosity who had produced a poetry at once superficial and mysterious. Its higher meaning, if it had one at all, was wrapped up within a flawed moment for British poetry which seemed likely never to be repeated. And that special aesthetic sensibility, if it had ever truly existed, the sensibility which enabled Pope and his readers truly to feel the difference between a varied softness and sweetness in English heroic verse, or to read in expectation that others may give and receive such feeling in fullness through poems written in its measures, had vanished along with it.

2. ‘Literal Truth’

Do not consider this as poetry. — Poetry on such occasions is no more than literal truth. In the present case it is less; for half the tenderness I feel is altogether shapeless and inexpressible.

William Shenstone, ‘135. To Richard Graves’ [Feb. 1748], The Letters, ed. Duncan Mallam (University of Minnesota, 1939), pp.239-40

‘Language is impersonal’, Denise Riley’s Impersonal Passions (2005) begins, ‘its working through and across us is indifferent to us, yet in the same blow it constitutes the fibre of the personal’. To speak of verse-sensation in Pope’s poetry as Rileyan linguistic affect, as feeling that electrifies the nervous fibres of the language of a literary poem, subtly displaces and extends the situative emphasis of what some eighteenth century philosophers of art would have called the aesthetic affections from the sentiments of the reader, to the work, and through the work toward the poet on the other side of the text. It refigures reader, poet, and poem as moments in a complex system of feedback dynamics, involving multiple active subjects and streams of feeling. This looks like a contradiction, because verse-sensation, if it’s anything at all, is a form of cognitive experience in the reading subject, stimulated by variances in the prosodic movements of literary poetry. As text, in its impersonal dimension as language-as-such, a poem can not by any objective material test be said to have the qualities we feel in it, for all that the metaphors we use to represent literary experience may suggest we believe otherwise. When we say this or that verse is rough or smooth, this is not exactly so. The roughness or smoothness we feel is not in the poem. But representing the truth of the subject’s experience in reading often calls for recourse to disruptive figures and contradictory terms. From the standpoint of that experience, as my own experience insists, language-as-such is the phantom, and the poem truly has the softness and the sweetness the reader feels, which we may rationalise by remembering that no poem exists other than as a vital cognition, as a moment or distribution of moments within a reader’s embodied being. And once this is grasped, once the poem, every poem, is known not simply as an object in language, but as a feeling event in cognition, the intimate promise of all poetry may be disclosed, and the poem as a cognitive content become known also as a container for all the intensities and vagaries, even the shapeless and inexpressible tendernesses, of the poet who made it.

And here things might begin to get very interesting for poets and their readers, because a poet who knows this, a poet who is not just a functionary in the creative process but a fully conscious creative artist, might make poems in the fullness of that knowledge, poems intended to unfold deeply intentionalised intimacies in the sensationally personal chemism of verse. I believe Pope to have been such a poet — so much so that he could also choose when not to be — and in the story I want to tell here about how he made his poems, in this little gathering of abandoned investigations, half-forgotten thoughts and digressions, begun in a time of breakdown and picked up again in a time of recollection, softness is not just another type of linguistic affect, but must be understood as something like its original or essential mode. My feeling for the secret of verse-sensation in Pope’s poetry lies among folds of softness: in the softnesses of his poems, their reader, and their poet, the son of a textiles merchant, raised in precious softness, whose disabled body was laced up tight into a stiff orthopedic corset of metal and bone every day in order that he could stand, who loved to be a moment of human softness encased in the hard gleaming surfaces of his garden’s subterranean grotto, and whose inward softness was perhaps the ultimate object of that disgust which later poets and critics would sometimes feel against the poet and the art he made, as it is also the source of that magnetism which draws me toward him.

⁂

For Pope, softness had a manifold and yet quite coherently organised and consistent set of meanings which endured over the whole course of his life. It is among the most important epithets in his diction, as it had been for Shakespeare, Spenser, Jonson, and Dryden, and for the poetic language of the seventeenth century as a whole, in which it is often to be found in proximity with ‘sweet’ and ‘smooth’, terms which even the period’s better poets habitually attributed to the very same objects they would call ‘soft’. Pope was, and wanted to be, a poet of finer distinctions, one who could really feel and make felt sensible differences in aesthetic experience. In Pope’s poetry ‘hush’d waves’ may ‘glide softly’; ‘hours, days, and years’ may ‘slide soft away’; ‘showers’ and ‘seasons’, may be soft, as might also the ‘labyrinth of a Lady’s ear’, snipped from Donne’s second Satyre, or an ‘obstetric hand’; so may ‘transitions’ between images, ‘minds’ and ‘memories’. In Pope’s poetry, softness is most usually either a quality of surfaces and things that yield to human touch, or of sounds and movements — especially of air, water, words and footsteps — when they are quiet or stealthy, but hearts and minds could also be soft sometimes, especially when they were especially mutable, or feminine, or receptive to impressions.

The word did not have this meaning for Shakespeare, who used it with crisp literalism. Spenser’s poems could scarcely be described as crisp or literal, overflowing as they are with soft breasts, soft sheepe, soft eyes and soft sighs — but not, I think, soft thoughts. Soft cognitions may be found here and there in the poetry of Ben Jonson, most notably in Under-Woods LXXXIV, ‘Eupheme’, a partially-lost sequence finalised by Jonson in 1633 comprising several praise texts written in in the 1610s. ‘Eupheme’ is a fragmentary elegy on Jonson’s muse (‘who living, gave me leave to call her so’), the aristocratic celebrity Venetia Anastasia Stanley, wife of the occultist and adventurer Kenelm Digby, one of Jonson’s most important courtly supporters. Digby was an adept of sympathetic magic, and a believer in the Paracelsian doctrine of weapon salve, which held that injuries might be healed through the ritual treatment of the wounding object. He was widely believed to have jealously murdered his wife under pretence of medication with a preparation called viper wine. During the fourth poem in Jonson’s sequence, a set of witty variations on the motives of his friend’s ‘Mind so rapt, so high’ for having descended to earth, he extols that mind as ‘Smooth, soft, and sweet, all in a floud | Where it may run to any good; | And where it stayes, it there becomes | A nest of odorous spice, and gummes.’

Pope extensively annotated this poem in his copy of the 1692 edition of Jonson’s works in his mid-teens, marking the stanza immediately preceding the above with a sigil denoting its special interest to him. That stanza contains one of the several figurings in earlier poetry of a thought to which his Essay on Criticism (1711) would give definitive expression, where Jonson’s ‘The Voice so sweet, the Words so fair, | As some soft chime had strok’d the Air | And, though the sound were parted thence, | Still left an Echo in the sense’ is melted, along with lines of Wentworth Dillon, Earl of Roscommon’s Essay on Translated Verse (1679), ‘Sublime or low, unbended or intense | The Sound is still a Comment to the Sense’, and perhaps other less convincingly attested texts, into Pope’s sylphid prescription: ‘’Tis not enough no harshness gives offence, | The sound must seem an echo to the sense’. Dryden only allowed softness as a quality of immaterial things when it was laid out in an extended metaphor, as on several occasions in his later works when he depicts a consciousness with the receptivity of warm wax — a metaphor also employed by the Augustan Latin poets in their several figurative uses of the cerae or wax tablet. Pope too uses wax in an extended metaphor for the mind in his Essay on Criticism, with an elegance not found in Dryden, who always seemed concerned that his reader might not grasp the figure’s meaning without having it made explicit over consecutive verses.

3. ‘ad auras | aetherias’

The sweet Enthusiast, from her Sacred Store, | Enlarg’d the former narrow Bounds, | And added Length to solemn Sounds, | With Nature’s Mother-wit, and Arts unknown before.

Dryden, Alexander’s Feast; or, The Power of Musique, An Ode in Honour of St. Cecelia’s Day (1697)

Though I made that last observation as though it were a throwaway line, it really contains the kernel of my thought about softness and verse-sensation in Pope’s poetry, which I want to come at again still more obliquely over the next few paragraphs by unfolding a few of the implications of the comparison Pope draws between Dryden and Edmond Waller. I don’t want to get too deeply into it, since a comparative reading of these two poets can become fiddly and complicated, partly because they are discovered to be ‘on the same points’ less often than might be assumed even when they share a topic and theme, and partly because even their minor poems can require some heavy contextualisation, which I would prefer to keep light. Waller was twenty-five years older than Dryden, and had begun a career in parliamentary politics fresh out of Cambridge before the revolutionary wars in which he acted as a royalist insurrectionary and terrorist conspirator. Unlike several of his collaborators, including his unfortunate brother-in-law Nathaniel Tompkins, Waller was able to bribe and weasel his way out of being executed after the detection of their plot in 1643, and escaped to the continent for a period of exile after successfully pleading for his life before Parliament: ‘something there is, which if I could shew you, would move you more than all this,’ Waller implored his former friends and colleagues, ‘it is my Heart, which abhors what I have done’. Following his return to England in 1653, his Panegyrick to my Lord Protector (1654) gained him a place in Cromwell’s state apparatus. The similarly adaptable Dryden also held a place in the bureaucracy of the Cromwell regime, and the two poets seem to have been on friendly terms. They would go on to keep their places in the stage-machinery of Stuart power after the Restoration of the monarchy, were members of the same clubs and societies, and disputed the art of poetry together in some detail, as references to their conversation and correspondence in Dryden’s published works indicate.

As poets the two men were very different. Though supported by aristocratic patrons and rents from the estate into which he had married through his alliance with Elizabeth Howard, daughter of the Catholic grandee Sir Robert Howard, one of Waller’s associates in the parliamentary wing of the pre-revolutionary autocracy, Dryden was by the 1680s close to something like a professional writer, drawing an income from the proceeds of his work in theatre, encomiastic and satirical verse, and translation. As a literary celebrity, obliged to contend for public attention, his poetry was contumelious, charismatic, and copious to the highest degree. Dryden wore the dignity of a public gentleman like a theatrical costume, even in the act of bearing intimate poetry to his reader’s ear. But Waller’s was never that kind of voice. His was a poetry of deeper sincerity, of anxiety and irony. His projects were typically modest and his statements reserved. Though he wrote prologues and commendatory verses when required, he resisted showing himself and his work importunately. This was in part a behaviour determined by the norms of his caste — which his militarising period was learning to call by its imperial name, rank — but my feeling is that he also found other people clumsy and cruel with poetry in general, and sensed that his own work, polished though it was, concealed a fragility he was unready to trust them with. His most convincing poems were twilight lyrics like the beautiful ‘Of the Last Verses in the Book’ (1682), and works of courtly humanist narrative argument like ‘Instructions to a Painter’ (1665), in which he would exhibit a rare and appealing vulnerability along with the more usual wit and correctness. He also wrote wonderfully sensitive, gently moralising epitaphs, and some hot amatory verse like the fetish lyric ‘On a Girdle’ (1645) — evidently once I start listing works of Waller’s that I admire it becomes difficult to stop, but he produced no single defining work to distinguish his achievement in poetry. He was regarded approvingly by the poets of his era as an innovator in the development of heroic measure, alongside other mostly-forgotten mid-century luminaries such as John Denham, and eighteenth-century critics during the supremacy of heroic verse would routinely pay him lip-service as such. But he was to my ear at his most attractive and accomplished when he wrote tetrameter stanzas in the manner of Jonson, whom he apostrophised in eulogy as the ‘Mirror of Poets, Mirror of our Age!’ He was able to turn such verses with a delightful blend of levity and intrigue, as in his Horatian ode ‘Of English Verse’ (1675):

Both Waller and Dryden were also translators from classical literature — Waller, in keeping with his general style, much less extensively than Dryden — and one of the few moments in their work where a direct comparison may be neatly drawn between their poetries can be found in their handling of a passage from Book IV of Aeneid which Waller translated in 1657 as a standalone poem, whilst Dryden would render the whole epic into English as part of his great labour of Virgilian translation, to be published along with the Pastorals and Georgics at the end of the century. Here are their treatments of one of the more famous extended metaphors in that section of the poem, the verses describing the determination of Aeneas to leave Carthage and pursue his fate in Italy through the image of a tree resisting a violent storm, as Queen Dido, through the ministrations of her sister Anna, pressures him to bend to her contrary wishes:

This comparison is fascinating to me, partly because Dryden clearly comments directly on his friend’s translation — which he would elsewhere gently traduce as a paraphrase — including all three of Waller’s rhyme pairs in reverse order and expanding the lines with new material, almost as though he is teaching Waller a lesson and correcting his work. I don’t think these are Waller’s sweetest lines, or Dryden’s softest, but the traits which I believe Pope felt as such in their poetries are sufficiently present here for us to work with. In broad terms, my idea is that the dual structure of a sensible difference between sweetness and softness in their verse begins from the differences between tetrameter and heroic measure, and the ways in which mid-seventeenth century poets had learned to develop the latter from the former, cutting back the gnarled and knotty iambic pentameter couplet they inherited from the Elizabethans, which found its defining expression in poems like George Chapman’s extraordinary The Shadow of Night (1594), to allow their supple new five-measure line to flourish in its place.

The attraction of working in tetrameter for treating complex subject matter, as Jonson had done in ‘Eupheme’ and as Waller had done in ‘Of English Verse’, lay in the interesting effects produced when poets tried to squeeze expansive thoughts and extended rhythms, which are often the same thing for the purposes of metrical composition, into the tight confines of the tetrameter grid. This compression naturally produced interesting events in the language of the poems they made, which tended toward a high level of internal tension as a result. Iambic tetrameter verse looks easy to make and easy to read — until its poet needs to say something in a phrase that doesn’t fit the frame. The obvious solution to this difficulty is to train the phrase across the line break and run it into the next verse — ‘But who can hope his Lines shou’d long | Last, in a daily-changing Tongue’ — which creates prosodic agitation and interest, but which will then leave the poet needing to do something about the surplus intensity added to a line which now only has two or three of its metrical units left to work with. A good poet will respond creatively to this further pressure, and perhaps create serial effects that redistribute the resulting concentrations of rhythmico-metrical energy over the verses which follow in ways which don’t mess things up to the point that the verse collapses, unless they want it to, and which might enable them to develop exquisite passing figures as the language slips and catches on the poem’s metrical lattice. The easiest way to get rid of this excess energy is to use stanza breaks, allowing silence to reset the poem as Jonson does to desperately brilliant effect in ‘Eupheme’. But if the measure is maintained over an extended period, and the intensity of the prosodic work increases, then, if that activity slackens even for a line, the poem will start to flake and peel, to lose its integrity and rhythm, and before long the seventeenth-century poet will start thinking about making their crumbling tetrameters into an irregular Pindarick ode instead. Maintaining the poem’s effects, keeping up the fetch-and-carry of rhythmised cognition, handling the quandraries of compression creatively, all while keeping just within the tolerances of the grid, leads to the form we might think of as the higher or noble tetrameter — a tetrameter that’s ready to grow another measure, but is holding back to keep things light and fresh, under the strain of bearing that burden which comes with trying to write about something serious in a verse form that resists our seriousness at every turn.

⁂

My feeling is that the sweetness Pope reads in Waller’s heroic verse is connected with this tendency toward prosodic over-ripeness in the shorter metre, because Waller approaches making poetry in the longer line in more-or-less the same way that he approached making noble tetrameters: putting pressure on the language to create moments of metrical surplus and deficit, filling up each verse with interesting events and effects, making moves with repeated sounds and phrasal structures, and bending the poem ornamentally around the metrical frame. The sweetness of Waller’s heroic verse is that stringent sweetness which sounds from a plucked string under tension, coating perception as honey coats the tongue, giving up a momentary pleasure which passes as the vibrations fade into echo, to leave disgusted aversion or an urgent desire for more. Pope and his contemporaries strongly associated this kind of sweetness with the renaissance lyric poets from whom Waller, according to Dryden in an anecdote in the introduction to his Fables (1698), claimed his poetical inheritance. Whereas ‘Milton has acknowledged to me, that Spenser was his original’, Dryden confidentialises, leaning in to share his secrets, ‘many besides myself have heard our famous Waller own, that he derived the harmony of his numbers from Godfrey of Bulloigne, which was turned into English by Mr Fairfax’. For Pope, who experienced verse with vivid sensations of taste and touch, Edward Fairefax, the Elizabethan demonologist and translator of Tasso’s Gerusalemme Liberata (1581) into Godfrey of Bulloigne (1600), would have bequeathed to Waller not just his harmony, but the sweetness of a freshness on the turn, the botrytic sweetness endemic among those poets who lived and wrote between the emergence of the Sidney circle and before the reform of English verse in the epic achievements of the later seventeenth century. The pentameter couplets that conclude Fairefax’s delicious ottava rima stanzas have a tendency toward excessive epigrammatic repletion, alleviated by the way in which, following Tasso, Fairefax often lets his sentences run over and across the stanza breaks, so that the couplet is rarely more than a weir or a swirl in the flow. The verses at the turn have tautness and solidity, whilst being at the same time elastic and porous enough to allow the long poem’s through-movements to continue from one formal space into the next. Waller’s fructose heroic measures could be thought of as something like Fairefax’s Romantic octaves with their sestets subtracted, so that the poems consist of nothing but spills and pools of honeyed phrases, flowing from and over and into cascades of disintegrating formal vessels — something as intricate, heady, and lovely as that.

Dryden goes about making heroic measures in a completely different and much more simple way, beginning with the obvious but essential truism that any line of regular lesser tetrameter could be made into a line of English pentameter by the addition of an adverb or adjective of two syllables, and expanding on the possibilities of this elementary insight to encompass the much more mysterious and interesting dimensions of what a poet could do — not just once or twice until the verse snapped, but over and over again without losing formal tension — with the luxuriant freedoms this introduced into the enlarg’d verse. The implications of rethinking heroic measure not as a reharmonised pentameter but as an expanded lesser tetrameter were and remain immediate and liberating. The move enabled Dryden to bring the ictus of line and sentence to coincide with less fuss and complication, which in turn meant that the division of the verse with a medial caesura could be elegantly maintained over successive lines and couplets without having to deal so frequently with the consequences of verses fractured by an intrusion of a grammatical or semantic surplus. This opened up the generous dimensions of the new poetry’s characteristic formal volume, the capacious Augustan verse paragraph, in which expansive thoughts and extended rhythms could be laid out in fluently extended periods, and gorgeously developed figures sculpted in verse. These innovations in heroic measure allowed its poets to shape their material like stuccatori, freed of the restrictions and resistances that came with composition in measures derived from the lapidary pentameter couplet or cracked anaphoric stanza.

Here is my earlier quotation from Dryden’s Aeneid, edited down into a serviceable lesser tetrameter. This was an easy enough task until I reached the last verse of the extract, in which Dryden handles a telling compositional problem in a way that encapsulates the almost comically exaggerated grandeur of his craftsmanship. The problem emerges from Dryden’s choice of the word ‘shoots’, which he used to capture the exciting movement of the tree in Virgil’s quantum vertice ad auras | aetherias, perhaps preferring the term because it helped develop the arborial figure. The most natural translation of Virgil’s radice in the verse which follows would be ‘roots’, which Waller uses. But the chime of ‘shoots’ and ‘roots’ introduces an ornamental starchiness to the verse which Dryden doesn’t want, and which he smooths away by getting rid of the roots altogether, replacing them with the stunning Drydenism — all Drydenisms are stunning — ‘fix’d Foundations’ in the final extracted verse. I couldn’t find a way to stitch that figure into a lesser tetrameter without unpicking the whole phrase, so instead I have allowed the line to twist back on itself, training the verse into exactly the sort of bind Dryden was trying to avoid:

When we return the descriptors ‘airy’, ‘Mountain’, ‘hollow’, ‘Royal’, ‘closely’, and ‘tow’ring’ to their places in these lines, the form is immediately plumped out with soft matter — airy sounds echoing in the hollow. Like the layer of curled horsehair that skilled upholsterers were learning to add to the stuffing pad in cushioned furniture-making during the 1690s, the dense softness of an additional layer of yielding material becomes the primary sensual characteristic of the work. The metrical cushioning created by the introduction of superflous quality terms to the lesser tetrameter verse then opens up the middle of the line, activating the heroic measure’s defining movement, the pirouetting variations of the medial caesura, now freed from that constant pressure which sweetens its more spirited and strenuous equivalent in the noble tetrameter and unreformed pentameter. This in turn allows for the development of rhythmic separation, drift, and return, without losing implicative tension between sentence and line, and these factors, especially as they interact over extended sequences of verses in the stuccoed architecture of the verse paragraph, I think may plausibly constitute the aesthetic structure of that linguistic-affective softness Pope claimed to have experienced in reading Dryden’s poetry.

4. ‘Breathings of the Heart’

I believe no one qualification is so likely to make a good writer, as the power of rejecting his own thoughts; and it must be this (if anything) that can give me a chance to be one. For what I have publish’d, I can only hope to be pardon’d; but for what I have burn’d, I deserve to be prais’d.

Pope, ‘Preface’ to The Works of Mr. Alexander Pope (1717)

Pope’s feeling for this kind of difference enabled him to work with aesthetic affections in his own poetry to develop the highest level of integration between metre, verse-sensation, and argument or narrative. So whereas a poet like me, just working at a simple editorial task like revising someone else’s heroic verse into tetrameters, might be limited to making decisions at the level of word-choice whilst observing simple principles of harmony — and still get it wrong — Pope was making decisions not merely between this or that word or measure, nor even between softness and sweetness, or hardness and bitterness, but between grades, intensities and combinations of aesthetic affection drawn from across the conceivable range of felt experience, and encompassing every imaginable degree of variance, whilst conducting a faultless craftwork of metrical composition almost as a subsidiary function of that higher labour. The language, up to a certain point, could take care of itself, which I take to be one helpful function of the much-derided poetic diction on which the heroic verse of his period relied, releasing the poet to attend that higher order of compositional work with the greatest possible freedom of imagination and expression. Thus the primary material of Pope’s poetry was in a sense not language, but what another critical idiom might call the objective content of aesthetic experience as such. And this leads to a problem still more extreme for the purposes of trying to write about how Pope made poetry, because if we take this possibility seriously, and hold it against the work that Pope actually made, then we must talk about the sensibility which phenomenalised that experience not simply as a reflex of the poet’s own cognitions, but as a back-formation developed from the poet’s ideations of the other, and convened in the phantom body of a third subject.

If this sounds cranky then probably it should, because it represents a scarcely warranted attempt to describe Pope’s way of making poetry by reading as a testament of his poetics a poem that was never explicitly designed or intended for such a purpose. This is not the Essay on Criticism, which really only teaches his reader how to read, or not to read, his poetry, but his Ovidian epistle ‘Eloïsa to Abelard’, written in the spring of 1716 as part of what might have been an abandoned project of modern heroides thematised by their explorations in poetry, sex, and the religious, including ‘Verses: To the Memory of an Unfortunate Lady’, written around the same time as ‘Eloïsa’, translations from Ovid including the very early ‘Sappho to Phaon’, written before 1707, and one of his burn’d works, a tragedy on the life of St. Genevieve, the guardian saint of Paris, written in his early teens. Pope seems to have tied off the thread that held these texts and preoccupations together with publication of his first Collected Works in 1717, perhaps feeling that with ‘Eloïsa’ he had reached a natural end to this putative line of thought. Deviantly reconsidered as a work of poetics, ‘Eloïsa’ thus presents a major poet’s beliefs about his art at a moment of their transformation, as one movement of thought and commitment gives way to another. From the cusp of new questions and a new understanding of his calling, Pope’s ‘Eloïsa’ attempts, with an ironic, proud, and surrendering generosity, to explain what her poet is trying to do, and to share the difficulties that he faces trying to do it — in a way that may also help to explain why, following its publication, this astonishingly capable young poet, not yet thirty, and in the full possession of all his gifts, didn’t write another original poem of any importance for a decade.

⁂

Here is my rendition of the familiar facts. ‘Eloïsa to Abelard’ is a dramatic monologue in the character of Héloïse, a distinguished abbess of the twelfth century. Héloïse had been compelled to accept life under the veil as a young woman following an unlawful relationship with Peter Abelard, Pierre Abélard, or Abailard, a noted theologian and logician. In 1115, Abelard, more than twenty years older than Héloïse, had been engaged by Héloïse’s maternal uncle, Canon Fulbert of the Cathedral of Notre-Dame, whose ward she was at Paris, as a private tutor for his gifted niece. Following the discovery of the sexual relationship that developed from their intellectual intimacy — which resulted in a child, the gloriously named Astrolabe — Abelard was castrated by vigilantes acting on the incitement of Canon Fulbert. The lovers, despite a secret marriage to legitimise their bond, were separated. Abelard, who appears to have been one of those teachers championed by their students and hated by their senior colleagues, was subjected to an ecclesiastical show trial at the Council of Soissons in 1121, during which he was forced symbolically to burn his own work on the trinity as an heretical text before a papal legate. He believed the event to have been corruptly managed by his academic enemies, who included most of his former teachers, and Bernard of Clairvaux, one of the most eminent men not just of the twelfth century but of church history as a whole. Bernard called Abelard a ‘herald of the Antichrist’, claimed that his intellectualism would ‘corrupt the faith of the simple, disturb the order of morality, and defile the chastity of the Church’, and persecuted him obsessively thoughout his subsequent career. Following this disaster, Abelard was confined to a monastic life. But like Héloïse, Abelard turned his confinement to brilliant success, continuing his work in teaching and administration, and playing a crucial role in magnetising the scholarly communities which would be combined to found the University of Paris at the beginning of the thirteenth century. Bernard would eventually achieve Abelard’s excommunication at the Council of Sens in 1140 after pleading directly to Pope Innocent for assistance, denouncing him in the most outrageous terms. The philosopher lived out the last two years of his life under the protection of his friend Peter the Venerable at Cluny, where he wrote the apologetic text that Pope’s Eloïsa is discovered having just finished reading at the start of his poem, Abelard’s confessional autobiography, Historia Calamitatum.

Abelard’s authorship was extensive. He wrote poetry, including a long poem of mostly extremely bad advice for Astrolabe, logical philosophy, and theology. He was a supple and elusive teacher, broadly interested in showing how dialectic could be used to resolve differences in the interpretation of church law and Christian doctrine without trivialising theological disputes or developing ever more narrow and exclusive orthodoxies, whilst remaining observant of Aristotelean precept and the Augustinian ideal of the sacred thinker. This stance involved him in bitter controversies with rivals who held that dialectic was strictly applicable only to its own disciplinary content, i.e. to verbal reasoning itself, whereas Abelard’s teachings seemed to promote dialectic not only as an instrument for identifying and correcting inconsistencies in statements, but for making ambiguous judgements about their essential truth. This became especially troublesome when dialectic was used to touch on verities that tradition held manifest beyond the limits of verbal reason, and discernable by faith alone. This narration of the career of Abelard as an intellectual rebel against reactionary ecclesiastical authority, which may be found in influential accounts such as that of Pierre Bayle’s Dictionnaire Historique et Critique (1697), itself originates from a pivot in interpretation that may owe more to dialectic or rhetoric than analysis — by which we accept the validity of Bernard’s charges against Abelard in his widely known animadversions, and then choose perversely to side with the argument that Bernard would have seen burn’d. ‘In this manner human wit is laying claim to everything’, Bernard fulminated, ‘keeping nothing back for faith.’

It is attempting things too high for it, searching into things above its ability; it is rushing into matters divine, defiling holy things rather than unlocking them; it is not opening things shut up and sealed, but tearing them apart; and whatever it finds inaccessible, it thinks of no account, and does not deign to believe it.

Bernard of Clairvaux, ‘Letter 188: To the Bishops and Cardinals of the Curia’, in R. M. Thomson and M. Winterbotton, eds. & trans. For and Against Abelard (Boydell, 2020), p.3.

Even had Pope known this text, or one of the several texts very like it, through recusant book and manuscipt networks, he would not have referred to Bernard’s writings openly. Works of Roman Catholic teaching and doctrine remained officially forbidden in Britain in 1716, and whilst others might have been able to get away with commenting on Bernard’s policy in public, it’s doubtful whether such an indulgence would have been extended to Pope. Abelard’s works themselves, beyond his letters to Héloïse and Historia Calamitatum, were almost certainly completely unknown to him, and had themselves been banned by the Roman church as recently as the late sixteenth century. Pope likely formed his ideas concerning Abelard and Eloïsa from their representation in belles-lettristic texts of the seventeeth century, including François de Grenaille’s Nouveau recueil de lettres de dames tant anciennes que modernes (1642), and a novelisation by Jacques Alluis, Les Amours d’Abailard et d’Héloïse (1675), as well as Bayle’s quite extensive entries on the lovers in the Dictionnaire. Pope may have met with these works in their originals, in translation, or in the popular English pastiche, Letters of Abelard and Eloise, made by the poet John Hughes and first published in 1713. The real interest for most readers of these stories, however, did not lie in the philosophical quandraries and ecclesiastical entanglements of Abelard, but in the erotic passion, originality of ideas, and miraculous candour of Héloïse.

⁂

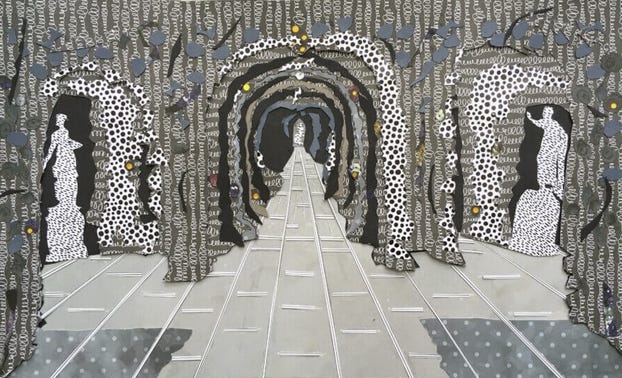

In Pope’s poem, Abelard is a silent figure addressed by Eloïsa in apostrophe. He represents impossible reason tormented by denied passion; Eloïsa represents impossible passion tormented by denied reason. Eloïsa longs for a consummative reunion between reason and passion, which would enable their torments to be redeemed, and reason and passion to be freed from their legacy of impossibility and denial. But Abelard was a eunuch, and is now dead, and Eloïsa is the surrendering captive of an inescapable prison, who spends her days swamped in melancholy and fantasy, and her nights chasing priapic phantoms around in dreams. Structural oppositions or dichotomies of this kind, with multiple values swapping their places across an axis of diremption, were often played out in the poetry of the seventeenth century, particularly in theological and devotional works, and I want to explore a last brief comparison before turning finally to Pope’s poem. Like that between Waller and Dryden sketched out in the previous section, this was also a comparison Pope invited, between ‘Eloïsa to Abelard’ and the work of Richard Crashaw, a poet clever in schematological composition, whose ‘Description of a Religious House and Condition of Life’ (1648) is quoted in Pope’s text. Crashaw’s ‘Description’ is itself an imitation of a neo-Latin poem drawn from the ultra-Catholic Jacobean courtier and agent John Barclay’s prosimetrical Romance Argenis (1621), which Ben Jonson had begun to translate before losing the work in a fire, at least according to a rather elaborate point of textual criticism built on the already rather dubious evidence of Under-Woods XLIII, ‘An Execration Upon Vulcan’. In Crashaw’s hands the moral diorama of ‘Eloïsa to Abelard’ might have been developed through an exercise in syllogistic processing like that which scripts the charming pornographia of Crashaw’s poem on the ecstasy of St. Teresa of Avila, ‘The Flaming Heart’, switching the positions of reader and poet, saint and seraphim, through densely ornamented corkscrew tetrameters: ‘Readers, be rul’d by me; & make | Here a well-plac’t & wise mistake | You must transpose the picture quite, | And spell it wrong to read it right; | Read HIM for Her, and Her for Him, | And call the SAINT the SERAPHIM’.

‘The Flaming Heart’ shares some phraseology and imagery with the ‘Description’, and the quotation from the latter is probably a bit of allusive bait-and-switch on Pope’s part. I am certain that Crashaw’s uncanny, horny, and incendiary ‘Heart’, and not his chaste ‘Description’, was the more prevalent in Pope’s mind when he was composing ‘Eloïsa to Abelard’, which I want to stress exceeds both poems in every conceivable way. A grasp of the shortcomings of Crashaw’s thrilling if rather brief and unsatisfying performance in ‘The Flaming Heart’ can help us to a deeper understanding of the structural poetics of ‘Eloïsa’, which I believe intended to improve on Crashaw’s example in this specific respect. Rather than swapping around his figures like pieces in a logician’s puzzle for the purposes of a theologico-poetical entertainment, Pope floods his figures with what he called in a letter to his friend Martha Blount, written during the last phase of the composition of the poem, breathings of the heart — rhythmised cognitions, vital and sensual, animating his substantives, loosening their internal cohesion, caressing them from their postulates, and gently teasing at their discretion. In Crashaw’s poem the ecstatic transfer of subject positions is an explosive event of climax and rupture, coming with a blare of metrical brass when the poem breaks into the pentameters that have only been sporadically ventured until this moment, but which are now unleashed in clerical frenzy:

Pope’s poem is suffused from its opening lines with the pressure of that heightened verse-sensation Crashaw steadily pumps his poem up with, achieving powerful and sustained modulations of intensity and subtle changes in emotional shading without needing to leverage disruptive moves like sudden changes of measure to amplify its images and ideas. Pope didn’t reject such theatrics arbitrarily. The insight of the poetics of ‘Eloïsa’ is that all verse-sensation begins in elasticity. Softness is not only a primordial aesthetic affection, and pleasing to the senses of the heart. Soft verse is a medium through which even a hard heart’s intimacies can be shared. I don’t dislike Crashaw’s poem at all, and I don’t think Pope disliked it either, quite the opposite, but few of its effects really land; and actually part of what’s likeable about ‘The Flaming Heart’ is the comradeship we might feel for the scholarly orgiast who wrote it, the bookish alumnus of Little Gidding thrashing around in his improbable spate of divine enthusiasm. But this is not the poem’s intended effect. Crashaw’s implicit idea of the relationship between a ‘bigge’ heart and a ‘bigge’ line is irreal and symbolic. I infer, rather than receive his feeling. And this is fine, so long as the reader is on his side, and wants the magic to work. But the best such a reader can do for Crashaw is some supportive noticing upon the poem’s artifice, as though it were a comment upon itself. Pope was making a poetry of another order entirely.

⁂

I want to literalise breathings of the heart in the poetics of ‘Eloïsa’ as a double movement that comprises at once a push-and-pull pulsation, and a gathering-and-scattering accentual complement — or to stick with the terms established in this essay so far, a softness that tensifies into sweetness, and a sweetness that loosens into softness, either which movement may act as pulse or accent over any given rhythmical expression. Actually this is the kind of movement that even Pope’s run-of-the-mill verse performs, so perhaps the artifice that makes the verse of ‘Eloïsa’ more intensely hedonic than any other verses in Pope’s poetry would be better termed a double-double movement, as each loosening-tightening is harmonised with a concurrent tightening-loosening. I sometimes like to dance with my hands to try and capture the movement of Pope’s measures: gripping and releasing pockets of air, turning my fingers in arabesques, concentrating and flicking away streaks of imaginary energy like a child playing at casting spells. The movements of ‘Eloïsa’ require both hands.

A vertical line of beauty curves through the centre of these verses, tracing the varied rest Dryden’s softness allowed English poetry’s enlarg’d heroic measure to sustain, and though it drifts at moments, as sweeter phrases replete the verse, it picks up again without any sense of interruption leading to fragmentation. There is no stiffness, brittleness, or grammatical strain. Sentence and measure curl and pulse in flowing agreement, and where work is done to concentrate and disperse prosodic energy, it seems an active choice rather than an improvised solution to an emergency, as in the ‘Rise […] rise’ envelope verse. But there is scarcely a line here that could be reduced to a tetrameter without tearing up its sentence. The softness of the verse has been so deeply worked into the language that superfluity is no longer helpful or necessary. This is softness without luxury. The consonances, internal rhymes, and alliterations in the hemistichs with a deeper medial pause — ‘dear ideas’, ‘stain all my soul’, ‘hymn to hear’, and so on — are naturalised in the verse-flow without displacement, producing integral effects, embroidered or damasked into their textures. The diagonal, or more appropriately the elliptical enchainments of the passing figures, developed over pairs or groups of verses, remain light and suggestive. This is important because it allows Pope to develop more of them, to develop figures from figures developed from figures, which is perhaps Pope’s most exquisite gift in composition. Ideas, voices, thoughts, rise, interpose, and swim, as Eloïsa burns and trembles in her images. At the same time, within and through these beautiful figures, the poem maintains rhythmical flow, with a wave-form much wider and deeper than the surface patter of iambicity, which doesn’t feel to me like a strong factor here at all. When we flood our reading with the countervailing sympathy the poem solicits, ‘Eloïsa’ becomes an immersive, intimate experience of dynamic transfer, its coherence not the outcome of patternated repetition, but mutation and exchange.

There are modes of verse-sensation in these lines, and throughout the poem, that I’ve not begun to think about in this essay. But more than anything in ‘Eloïsa’ there is softness, softness in verse-sensation and in image, softness in argument and in form. Into whatever combination the moments of its schema are recomposed, in whatever direction its movements are run, ‘Eloïsa to Abelard’ yields. The beloved object Abelard is soft, because his body has lost its capacity for sexual hardening; he is a philosopher of duality and irony; he surrendered manhood to l’amour. The loving subject Eloïsa is soft, because she is a woman; she made an écriture of pleasure; and she is full of receptive female desire. The poem itself is soft, because its measures frolic in the plump stucco flow of the heroic measure innovated by Dryden, brought in this poem to a perfection that even he might have blushed at; the elasticity of its structural movement allows Eloïsa’s periods and figures to stir, to pause, to stray without resistance; its schematological movement is soft, because its moments are stirred with breathings of the heart. The poet is soft because he is full of Eloïsa. He has wrapped himself in softness, filled himself with soft cognition, until almost, almost nothing remains of himself but softness, as he longs in masquerade for Abelard’s vanquishing ambiguous softness; and I am soft when I am its reader, because in my absorption, even in my distraction, the whole content of my being is replete with the softness of this poem, the softness of which is at once absolutely my own, absolutely its poet’s, and absolutely that of its third subject, the Eloïsa in and through which this absolute identity of three subjects is realised.

My heretical reading ramifies in the final movement of Pope’s poem, when Eloïsa reaches across the soft gulf of space and time to Pope, her ‘future Bard’; which I experience as a moment of the overwhelming invasion of an intimacy not with her, but with him — the consummation that this poem, Eloïsa’s testament of Pope’s poetics of sensible difference, may really have been working with and toward all along:

What Abelard is to Eloïsa, Eloïsa is to Pope, and Pope is to me: a soft figure through and in which to know my own softness, to search into things above my ability, and to believe or disbelieve, to act or not to act, beyond the limitations of my own understanding and powers. The more strongly I identify with Pope, the more intensely I love him, this broken and abjected man whose image I have exalted in my heart, and the more deep my gratitude for his poetry grows, then the more intensely felt and the more enabling this relation becomes. We can’t read Pope any better than Johnson or Coleridge, who should have known better, whenever we neglect this fundamental attitude of grace in the presence of sincere work. The testament of Eloïsa reveals this mystery to the discerning faithful: that Pope’s verses are not made by counting feet or syllables, varying the placement of the medial caesura, chiming the ends of the lines in couplet pairs, and using poetic diction to ornament ordinary language with worthless tinsel, as his contemporaries mistaught. They are made by exerting powers of identification and sympathy with the shameless, libidinal, liberated maximalism of Eloïsa, across the bounds which confine our wounded sovereignty and immiserated subjectivity into what only appear to be hard compartmental distinctions — categories which cannot even really survive the pressures exerted by an imaginary desire, felt for a phantom, in the dreams of a poet’s longing figment — to accomplish what Pope’s severally burn’d, neglected, abandoned and denigrated heroides were intended to accomplish: the elevation, consolation, and delight of hearts in flame.

⁂

I don’t think Bernard would have liked Pope’s poem any more than he liked Abelard’s dialectics. The problem with people like Pope and Abelard, for people like Bernard of Clairvaux, is that they are just not frightened enough of what he would call ‘the tyranny of the devil’, an absolute of Bernard’s faith, in which the crypto-Arian or proto-Socinian Abelard seemed actively to disbelieve, and in which Pope shows no interest whatsoever. The devil Bernard believed in was a god of torture, whose powers the Church exploited to terrorise the world into fealty. But our disgraced eunuch philosopher and our disabled poet did not fear pain, or not in the way that Bernard might have expected and preferred. There was no life without pain for Pope or for Abelard. The analgesia that Bernard seems to regard as the optimum condition of the soul, the cause and justification for all his savage policy, did not hold the same compelling power over them as it did him. Bernard’s understanding of the human was autarchic, narrow, profoundly sexist, and mechanical. Pope’s was not. Pain is prominent in Eloïsa’s cravings. In her dialectic, pain that stiffens, contorts and tightens the body, pain that should be the negation of softness, the fear of which should cause us to abandon all elasticity in favour of brittle compaction, like Bernard of Clairvaux and his church militant, wrapped in steel costumes to kill and mutilate the disobedient, becomes sublated as quality, an affective content that can be transferred between moments in a coherent softness without rupture:

There’s a horrifying abundance of pain in and behind the stories this essay comprises, an odious burden of killings, cuttings, and burnings. Waller on his knees to plead for his life before parliament. His comrades, hanged in the streets before their London homes. Dido climbing onto her funereal pyre. Virgil ordering the Aeneid burned from his deathbed. Abelard’s soft genitals under the knife. Abelard burning his book. Héloïse, abused by Abelard. Héloïse, separated from her son. The convent of the Paraclete in flames. The bodies of the lovers exhumed and moved, and exhumed and moved again, and again. Kenelm Digby watching while Van Dijk sketches Venetia’s corpse. Ben Jonson’s right thumb, branded with an M, pressed against his pen as he wrote poems in Venetia’s praise. The cup at her lip. The manuscript of Jonson’s translation of Argenis burning in his desk, with all his other secrets. Teresa of Avila, pierced by the seraphim’s dart. Pope’s early pages curling into smuts and embers. His softer, younger hand on the paper. This moment in my thinking about Pope’s poetics is fraught and tender. I have already taken extensive liberties with Pope’s poetry and ideas, as to my shame I do in all my storytelling about other people’s writing — but here I begin to anticipate the argument of the second part of this essay, so I must break off these reflections. Though he treated it lightly in this poem, I believe this encounter with the issue of pain, occulted within Eloïsa’s poetics of softness, would have troubled Pope very deeply. He would not return to his own poetry in a serious way until he had nested this problem, along with several others that emerged in his earlier work, in the ecumenical and humanist philosophy of love elaborated in An Essay on Man (1733-4). But the problem of how and what we feel in verse-sensation, the problem embodied in the relation between softness and pain in the dialectic of Eloïsa, would unfold implications reaching far beyond the limits of any humanism Pope could have conceived.

Our story will continue in Part 2: ‘Tu—whit! ————Tu—whoo!’

This essay is indebted to the work of Tom Jones, in particular to his book ‘Poetic Language’ (2012). It is almost entirely reliant on the extraordinary scholarship of Constant Mews for its information on Abelard and Héloïse. Rebecca Mannheimer’s 2008 essay on Pope’s annotations of Jonson is the sole source of my knowledge about them. My reading of Dryden and Waller borrows heavily from Saintsbury’s cheerful, bungling narrative in ‘The History of English Prosody’ (1906-10).