Dark Soul

Ralph Chubb x Hidetaka Miyazaki

TW: This short essay contains extensive references to historic child abuse, along with discussion of images and narratives which deal insensitively with themes of sexual violence and the exploitation of children.

Through the identification, or let us say, introjection of the aggressor, he disappears as part of the external reality, and becomes intra- instead of extra-psychic […] When the child recovers from such an attack, he feels enormously confused, in fact, split — innocent and culpable at the same time — and his confidence in the testimony of his own senses is broken. || Sándor Ferenczi, ‘Confusion of Tongues Between the Adult and the Child’ (1933), in Final Contributions to the Problems and Methods of Psycho-Analysis, ed. Michael Balint (Karnac, 1994), pp.156-67 (p.162).

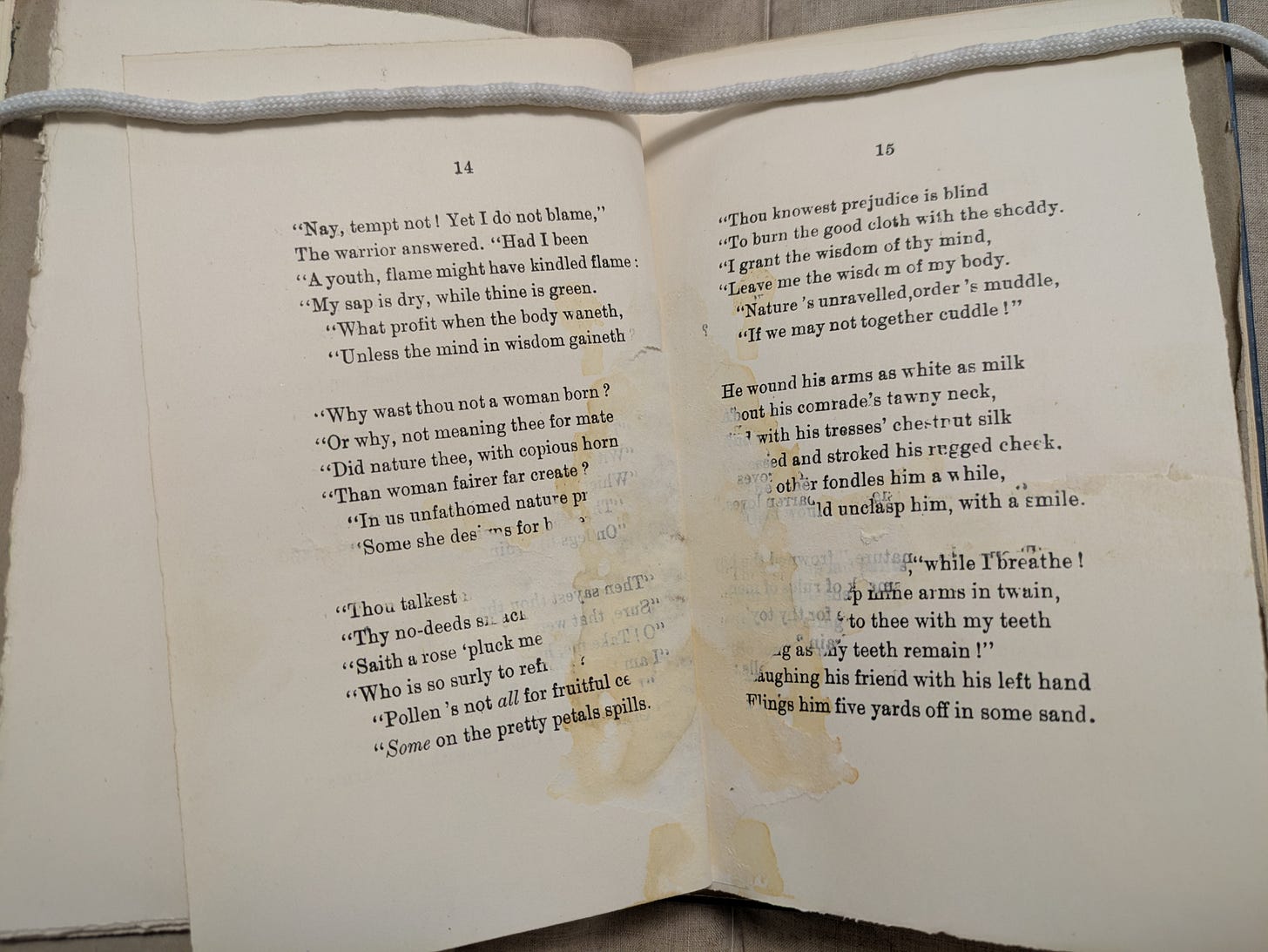

The copy of Ralph Chubb’s narrative lyric A Fable of Love and War: A Romantic Poem held in the Rare Books collection of Cambridge University Library is one of only forty-five to have been printed. Chubb was a Cambridge graduate, having studied classics at Selwyn College before the Great War, during which he was dismissed from the British army on grounds of mental unfitness, having attained the rank of captain, before attending the Slade School of Art after the armistice. He donated copies of all his books, printed in a workshop attached to his picturesque family home in rural Hampshire on a hand-press built by his brother, to the University Library over the course of the next thirty or so years, several of them with autograph notes and comments glued into their covers. As the printed archive of a unique creative life during a period of national and personal catastrophe, these books are precious, in their way. Chubb was an openly homosexual writer, making work focused on homosexual images, narratives, and themes, decades before the dawn of the permissive society in Britain. As such his work possesses innate value as a cultural document. But the UL’s copy of this particular treasure is in poor condition. Its hand-printed pages have been stuck together by a viscous, colourless fluid, emitted in a splurge down the gutter of the book. The yellowing stains left by this event penetrate through the printed material, both before and after the pages over which the fluid was spilled. It appears the book was not quickly cleaned, as one would expect in the event of an accidental spillage, but was instead deliberately closed over the spoiled pages, presumably in order to soak the paper, and more deeply to impress the sticky emission into the book’s luxuriant laid paper leaves.

At some point, though whether that point came before the book was accessioned to the UL or afterwards has proven impossible to discover, someone was stimulated to climax over this book, and sealed the pages with his semen. The pages over which he chose to ejaculate display the stanzas comprising the climax of the poem, in which a ‘stripling’ with ‘arms as white as milk’ is fucked by a ‘stalwart veteran’ whom the boy, depicted in Chubb’s woodcut illustrations as a hairless adolescent, has been pestering for sex in a moment of respite behind the front lines of an English war on foreign soil. ‘Pollen’s not all for fertile cells,’ Chubb’s ephebian seducer wheedles from the cum encrusted paper, ‘Some on the pretty petals spills’. Like much of the rest of Chubb’s work, A Fable of Love and War is a disturbing poem, in which distinctions between memory and intention, fantasy and desire, are dislocated and confused. In a brief foreword, Chubb presents this work as an ontological allegory in vindication of a system of personal beliefs derived from Uranianism, the Victorian educational movement which sought to normalise and propagate the sexual exploitation of boys by older males, to which Chubb had perhaps been first exposed as a pupil at the ancient public school of St. Albans during his own boyhood, and which he could hardly have avoided as a student at Cambridge in the 1910s. Styling himself ‘the Adept Radulphus Uranius’, Chubb elaborated this system in the artisanal books he produced over the 1920s and 30s, several of them painstakingly lithographed in the poet’s own handscript. According to a note pasted into the back cover of The Sun Spirit (1948), the most ambitious of these books, The Child of Dawn (1931), took him seven years to make. These texts were not thrown out onto the page in spasmodic fits, but were the productions of deeply committed and time-consuming processes of reflection, composition, and fabrication.

Uranianism was a neo-Hellenist ideological formation which sanctified institutional child abuse as a necessary component of imperial pedagogy during the drawn-out era of mandatory sex segregation in British education. In the late Victorian period, Uranian educators and ideas were endemic in the upper class boarding schools and at Oxbridge, notably at Eton and King’s College in Cambridge, where the most widely known of the Uranians, the poet William Johnson Cory, was both a master and fellow. Shielded by his accessories in the state bureaucracy, Cory groomed and abused boys and young men under his care over three decades, until finally being forced discretely to withdraw from public life in the 1870s when the parents of a student at Eton found intimate letters being passed between Cory and their son and threatened disclosure. The sexual subordination of boys to the pederastic passions of their masters was accepted by the British elite of the period as a means of producing a ruling class like that which had presided over imperial Rome, or the empire of Alexander, an autarchic male leadership phalanx annealed by forces the Uranians mystified under the title of love, but which might be more properly understood as shame, violently imposed upon its members during childhood by leveraging that mechanism of psychosexual domination the horrified Ferenczi would describe in the 1930s. The pathological splitting Ferenczi observed in reactions to affective stimuli among those disturbed by the mechanism of introjection, so disabling to the development of healthy adult selves, would enable a class of selves sickened by abuse to act with the ruthlessness and decision required to rule empire without getting caught up in unprofitable feelings like pity and compassion, especially for those human objects not esteemed interesting or beautiful enough to warrant sentimental attention.

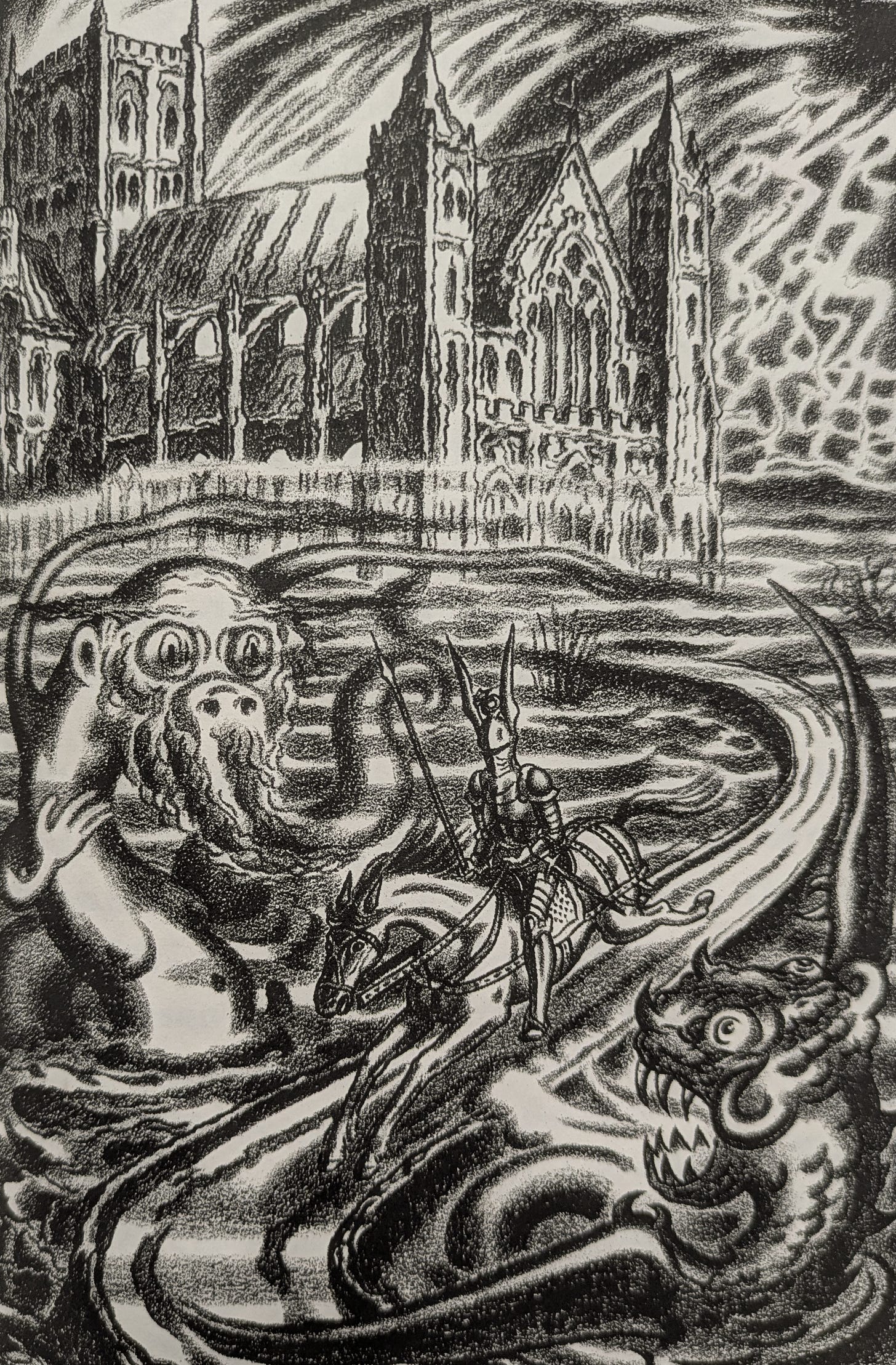

While there is interest and beauty in Chubb’s work, particularly in its exquisite lithography and book-craft, there is little sense of truth, though Chubb as a good Nietzschean would probably have seen himself as beyond such trivial concerns. Outside a handful of works which aspire toward another kind of relationship with experience and reality than hallucinatory play and gratification of the ego, Chubb’s writing in general shows none of the agitation with which an authentic drive toward what there really is — in memory, or perception, or external things — marks our poems. Chubb is a poet not of negation and discovery like William Blake, nor even of disgust and confession like the similarly troubling Francis Thompson, but of concealment and display, if that distinction can stand, in whose poetry the real and unreal blend without any evidence that the poet has faced the difficulties which come with trying to sort one from the other. His work is deformed by what I imagine to have been a life of oppressive, convulsive, and repetitious mental rupture. He fetishises tender memories of boys bathing and fantasises about predating on vulnerable children in the East End of London as though he doesn’t know the difference between sex and violence. He makes images of gleaming knights-errant embarked on senseless quests in service to the desires of grizzled kings, in which phallic symbolism is not a means by which to communicate atavistic suggestions, but is the entire goal of the act of representation. He anxiously encodes his criminal desires in occult cryptograms, whilst celebrating them as the rights and dues of innocence and freedom. The pathological character of Chubb’s sexuality may be sensed most acutely in the impersonality and disassociation the reader encounters at those moments in Chubb’s poems and stories at which the reverse might be expected to prevail. Sexual gazing is a hygeine inspection. Sexual speech is vacuous curial incantation. Sex itself is an experience of magical surrender, cleansed of messy consequences. Needless to say, his dread of women, with the exception of his sainted mother, is pervasive and absolute.

❖

In the Dark Souls trilogy of video games (2011-16), developed by From Software under the direction of lead designer Miyazaki Hidetaka, players set at risk a collectible resource called ‘humanity’ in order to enter each other’s online play sessions as ‘phantoms’, either to assail other players as opponents, or to assist them against other player assailants or non-player enemies, in passages of what one of the games’ most celebrated characters, the hearty Sun Knight Solaire — who sports a sunburst device on his tabard, coincidentally similar to that of Ralph Chubb’s Leam de Leall in Child of the Sun (1948) — calls ‘jolly cooperation’. The games are set in convoluted, intenstinal environments, infested with monstrous enemies, comprising poisonous swamps, gloomy woodlands, and elaborate Gothic structures on the scale of Piranesi’s Carceri. Defeated enemies expire in sprays of shimmering silver ephemera, as victorious players collect their ‘souls’ to spend on upgrades to their characters and equipment, enabling them to take on the champion foes or ‘bosses’ that stand eternally waiting for the player to challenge them behind grey ‘mist doors’. Softly spoken feminine spirits encourage the players to persist in mysterious quests, confronting combat challenges of increasing difficulty and complexity, for purposes which are rarely made fully transparent, but which typically imply some form of transcendence of the constraints of mortality or cosmic law through sacrifice, and the destruction of a decrepit absolutism. While the visual and narrative sources for Dark Souls are widely distributed in Japanese pop culture and in British literature and visual art of the later Romantic period, with strong echoes of Tennyson’s Idylls of the King and the iconography of the pre-Raphaelite circle, its most important and immediate influence is the work of manga artist Miura Kentarō, creator of the Berserk series of graphic novels (1990-2021).

The protagonist and antagonist of Berserk, the hyperbolically endowed swordsman Guts and his nemesis, the narcissistic paragon Griffith, are both revealed in flashbacks disclosed over the course of the more than forty volumes of Miura’s unfinished pulp fantasy saga to have been survivors of childhood sexual abuse by adult men. Those experiences drove Guts and Griffith to become superhuman avengers, sealing their soft bodies within rigid armour relentlessly to pursue release from anxiety, and are represented by Miura as causal links in the development of the two characters’ disturbed adult sexualities. Like Chubb, Miura set his fables of sexual cruelty in a world of Gothic citadels and wilderness, haunted by Thalassian monstrosities and the undead, in an epoch of war-torn desolation. Like the knightly figures of Ralph Chubb’s Uranian phantasmagoria, the warriors of Berserk inhabit a world dominated by the psychopathologies of phallogenicism. Unlike Chubb, Miura would not only represent but amplify the messy consequences of abuse. His characters act out doomed positions in the struggle against introjected guilt and the legacies of violence. In a strong contrast with the rules of Chubb’s enchanted pornotopia, Miura’s commitment to punk truism maintains a moral resistance against the most obvious kinds of exploitative idealisation. This schemata produces some strangely tender and moving scenes, most memorably during the sequence in the cycle’s classic Golden Age Arc in which Guts experiences intrusive memories of childhood abuse that cause erectile dysfunction and a psychotic episode in his first attempt at consensual lovemaking with Berserk’s heroine, the boyish Casca. Yet outside such moments Miura’s casuistry and tragic fatalism are clunky, ideologically narrow, and psychologically fanciful. The schematology of Berserk is no less fantastic in human terms than the imperialist delusions indulged by Tennyson in the laureate superstructure of his Arthurian cycle, and lie closer to the generic and obvious tropes of a desultory pornography than a meaningful creative response to the annhilating power of introjection.

If there is no truth in Ralph Chubb, and the wrong kind of truth in Miura Kentarō, might there be truth in Dark Souls? Although the game’s austere, punishing game loop, in which players must ‘die’ and reattempt to overcome the same obstacle repeatedly until they succeed in order to move forward on their obscure quests, superficially promotes a disciplinarian ideal of skills competence, by which incremental improvements are achieved only through sustained bouts of failure as players strive to ‘git gud’ enough, as the subcultural idiom puts it, to overcome the world’s resistance, typical player experiences of invasion, instead of testing battle reflexes, strategies, and tactical adaptability, will comprise spontaneous inspection rituals in the free-form metagame known among players as Fashion Souls, clumsy attempts at communication using the in-game system of awkwardly animated character gestures, and combat encounters defined by puerile clowning and the exploitation of comically unbalanced game mechanics. Dark Souls formally sets out its systems before its players as tests of prowess and moral resilience in the face of entropy. And sometimes, late at night, ten hours into another playthrough, a dozen or more attempts deep into a lonely struggle against one of the games’ daunting boss fights, running low on humanity and with your carefully hoarded souls long since lost, it can sometimes feel something like that. But more usually, at the level of praxis, Dark Souls orients us toward levity and camaraderie. Just as Ralph Chubb’s work appears to be a joyful exhibition of sexual disinhibition, and is really an oppressive vindication of the abuser’s rights of violation, Dark Souls may appear to be a form of disciplinary male activism in the pursuit of a proto-fascist dream of mastery, but is really about anarchic collaborations in carnivalesque acts of disobedience that make a mockery of the master’s claims to dominion.

Ralph Chubb did not become a superman. Uranian sexual exploitation did not turn him into a psychotic avenger, any more than it enabled him to unlock the sublime capabilities of true genius in his work in poetry or visual art. Institutionalised child abuse in the schools of our depraved and blundering upper class did not cause the British empire to become a transcendent administrative enterprise staffed by a service caste of sadistic angels. It simply produced stupefaction and inertia. The sublimation of introjected childhood shame in adult activities, like making erotic prints, designing video games, or running a state bureaucracy, is revealed not through the subject’s elevated performance of functions in cultural rituals and control systems, but in the affective discontinuity described so lucidly by Ferenczi in ‘Confusion of Tongues’, which at its most extreme may render the subject incapable of adopting the most basic preliminary postures required for cooperation. When I read Ralph Chubb complaining in his pasted notes of the failures of those around him to meet his excessive and elaborate demands for assistance, they do not seem to me the statements of one prepared for dutiful service in an inhuman state machine, but of an irretrievably damaged neurotic, barely able to accomplish his own designs, let alone to administer those of other people. What most alarmed Ferenczi about the abuse that clients had been telling psychoanalysts about over the previous fifty years was by 1930 not simply that childhood victimisation produced shattering neuroses that overthrew adult selves, but that such abuse appeared to be so widespread as to be virtually ubiquitous in a social body whose means of making communicable sense of its self-experience had been disrupted by the very same violence it most needed to talk about.

Like untold numbers of other children of my generation in Britain, as a small child at primary school, in a pauperised former pit village in County Durham in the early 1980s, I was subjected to sexual interference under cover of a health inspection conducted by an adult male teacher and doctor. The things they said and did during this abuse, which lasted no more than a few minutes and only occurred once, have remained fiercely imprinted on my memory for more than forty years — though whilst being fiercely imprinted, those memories are also vague and unreliable, their content invaded by what I know to be impossible details, and the projections of later surmises. My internal responses to these memories when they intrude on my conscious mind do not produce in me that clarity of purpose which drove Guts and Griffiths to seek out and punish their abusers. They are muted and incoherent. Whilst abstractly I recognise the images in which these memories might be said to consist as the impressions of sense perceptions experienced by my own organic self at an earlier point of existence, they don’t come with the sprung affectivity of more robust and complete recollections. They are hollow and skeletal. The encounter with these moments produces not a concentration of feeling but diffusion and numbness. To sort what is true from what is not, what happened from what did not, seems vitally important when I face that vacancy. In common with many of the poets I most cherish, I am drawn to seek for truth urgently there, at that moment in thought when the subject meets the void. I’m always talking about dialectic in these essays, in such a way that it might seem to informed readers that I don’t know what the word means. But I feel sure that the drive of dialectic, whatever that might really be, can not be an unmotivated reflex of its content. It must originate in the will to know, the need to make truth from our materials, howsoever disparate and inert they may be when we begin. If there is truth for poets in Dark Souls, as I hope there is, then let it be the kind of truth discovered in our ludicrous invasions, in spontaneous and disobedient play in defiance of death and boredom, with the tokens of our humanity at stake, and not the kind of truth only promised as a reward at the end of our service to a master’s fatal demands.

Thanks to Elizabeth Stratton, college archivist at Selwyn and Clare, for her generous assistance, and to the staff of the Rare Books and Manuscripts Reading Rooms at the University Library.